INSIGHT by Kerstin Lopatta, a full professor at the School of Business, Economics and Social Science at the University of Hamburg.

ZOOM IMAGE © Bassen/Lopatta/Kordsachia[/caption] The EU-Taxonomy, a light at the end of the tunnel in the non-financial reporting landscape? The global and European non-financial reporting landscape is characterized by a confusing variety of different standards. Even the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD) and the supporting non-binding guidelines do not recommend one common standard. Therefore, the so called EU-Taxonomy might be an important step towards a generally accepted non-financial reporting standard. I will shed light on the design, advantage and challenges of the taxonomy.In June 2020 the EU published Regulation 2020/852 (“EU-Taxonomy Regulation”) which fundamentally transforms the European regulatory landscape with regards to mandatory non-financial reporting requirements of companies and other financial market participants.To that end, the EU-Taxonomy maps corporate economic activities into one of the following six environmental objectives:

ZOOM IMAGE © Bassen/Lopatta/Kordsachia[/caption] The EU-Taxonomy, a light at the end of the tunnel in the non-financial reporting landscape? The global and European non-financial reporting landscape is characterized by a confusing variety of different standards. Even the non-financial reporting directive (NFRD) and the supporting non-binding guidelines do not recommend one common standard. Therefore, the so called EU-Taxonomy might be an important step towards a generally accepted non-financial reporting standard. I will shed light on the design, advantage and challenges of the taxonomy.In June 2020 the EU published Regulation 2020/852 (“EU-Taxonomy Regulation”) which fundamentally transforms the European regulatory landscape with regards to mandatory non-financial reporting requirements of companies and other financial market participants.To that end, the EU-Taxonomy maps corporate economic activities into one of the following six environmental objectives:Climate change mitigation

Climate change adaption

The sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources

The transition to a circular economy

Pollution prevention and control

The protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems

In order for an economic activity to be considered in alignment to the EU-Taxonomy, it needs toSubstantially contribute to at least one of the six environmental objectives,

Do no significant harm (DNSH) to any of the other five, and

Comply with minimum safeguard (i.e. alignment with the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights).

An economic activity can qualify as contributing substantially to one or more of the environmental objectives on the basis of itsOwn contribution

Direct enabling ability as regards to other activities that make a substantial contribution

Support for a transition to a climate-neutral economy (only applies to environmental objective of climate change mitigation)

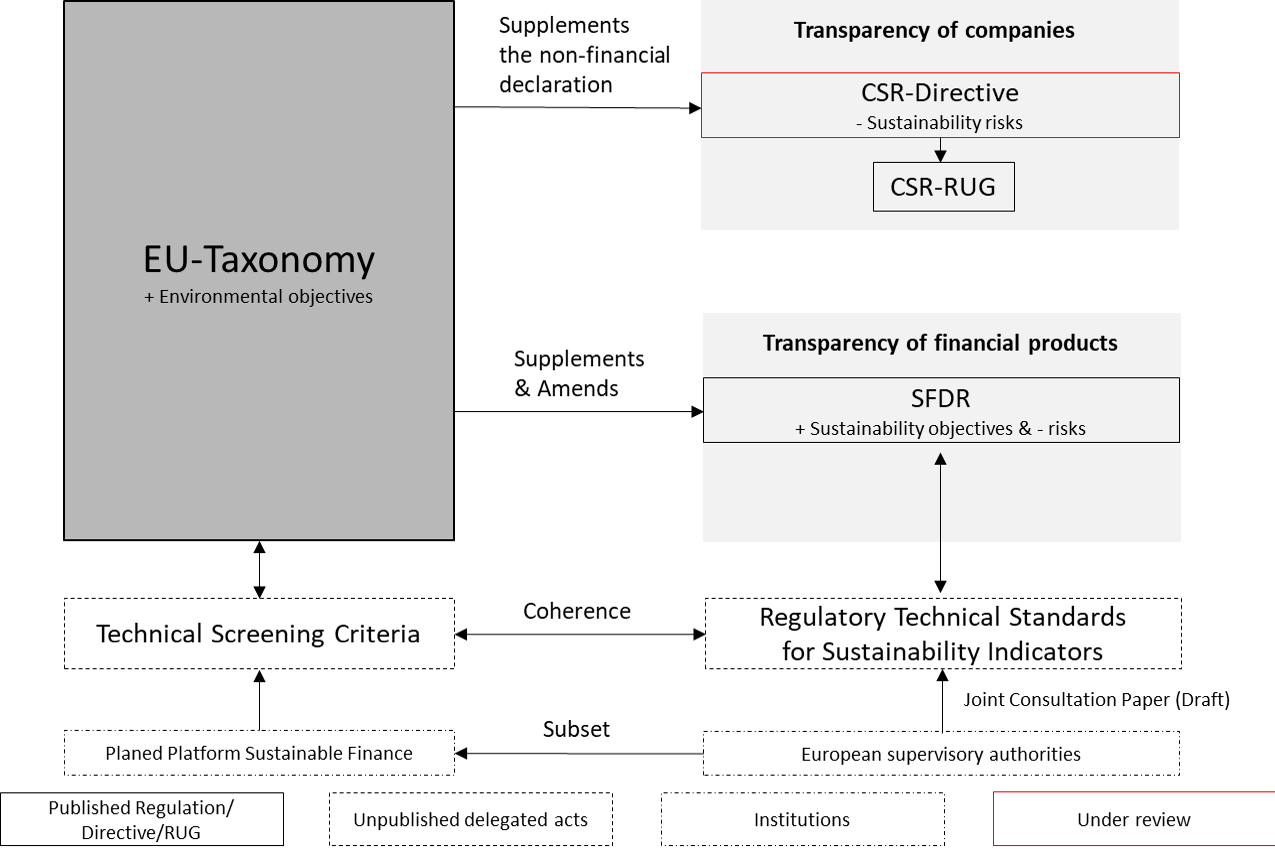

The EU technical expert group on sustainable finance (TEG) developed detailed “technical screening criteria”, which, in essence, define specific measures and thresholds for the EU Taxonomy-alignment of certain economic activities. Right now, the technical screening criteria are only available for certain industries with high CO2 exposure or industries that enable the transition a low carbon economy. Therefore the technical screening criteria are of high relevance for the implementation of the EU Taxonomy and they determine what has to be reported. Companies have to show in their financial statements which revenues, capex and opex they generated with the EU-Taxonomy aligned activities. Interested parties may gain a glimpse into the scope and complexity of the EU-Taxonomy by inspecting the technical annex to the TEG’s final report that was already published in March 2020.The EU-Taxonomy Regulation prescribes a staggered approach in this context. The first delegated act pursuant to the first and second environmental objectives - the ones specifically pertaining to the achievement of broader EU climate goals, like for example, a net zero emission economy by the year 2050 - shall be adopted by 31 December 2020. The second delegated act subsequently establishes technical screening criteria pursuant to the remaining environmental objectives and shall be adopted by 31 December 2021. Is this timeline impressive or scary? Transparency requirements of financial market participants (Disclosure Regulation) One important consideration in the further development of the technical screening criteria is their consistence with the “regulatory technical standards for sustainability indicators” (RTS) as put forth in regulation (EU) 2019/2088 of 27 November 2019 (“Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation”, SFDR). These indicators have to be developed by the European supervisory authorities (ESAs) and shall determine the transparency requirements of financial market participants as regards to sustainable investment objectives and the risk of adverse sustainability impacts. Together with other members of the platform on sustainable finance, the ESAs will be responsible for coherence between the DNSH-principle of Article 17 of the EU-Taxonomy and the sustainability indicators in relation to adverse sustainability impacts as described in Article 4 of the SFDR. The regulatory frameworkThe figure above illustrates the regulatory framework regarding non-financial disclosure requirements in the EU - including relevant regulations, directives, delegated acts, and institutions.The framework visualizes how the shifting transparency requirements due to the EU-Taxonomy significantly depend on the design of the technical screening criteria. Their formulation will have a direct impact on the disclosure of companies as well as the disclosure associated with the supply of financial products.Any companies that are subject to obligatory publication of non-financial information as per the Directive 2014/95/EU (“CSR-Directive”, also “NFRD”) will have to cope with significant supplementary disclosures.These requirements shall apply from 1 January 2022 for the first and second environmental objectives. Assuming financial statement publication in 2022, this means that large companies need to, in part, already apply the EU-Taxonomy for their 2021 disclosures. Full application of the EU-Taxonomy including all six environmental objectives becomes obligatory one year later.The current review of the CSR-Directive may additional increase corporate transparency obligations. The public consultation on non-financial reporting by large companies identified a number of problems. A majority report addressees attested deficiencies in terms of comparability, reliability, and relevance. In contrast, preparers of non-financial information identified additional requests for information from rating agencies and NGOs as a significant problem. Interestingly, some companies claim to face already problems regarding the current level of complexity and deciding what information to report.In general, the consultation unveiled strong support for a requirement on companies to use a common standard, stricter audit requirements, and disclosure of materiality assessment processes. These results may contribute to a possible amendment of the CSR-directive, which could increase the extent, the contents and the scope of non-financial disclosure.For example, the inception impact statement concerning the European Commission’s initiative to amend the CSR-directive considers requiring some or all companies under the scope of the legislation to use a non-financial reporting standard. This may substantially reduce managerial leeway in non-financial reporting choices and strengthen comparability and usefulness of disclosed information for institutional and retail investors.Providing high-quality information to institutional investors is particularly crucial due to investor’s own transparency requirements pertaining to the SFDR and its amendment by the EU-Taxonomy.

For example, in the case that sustainable investment objectives are linked to a financial product as per Article 9(1), (2) or (3) of the SFDR, the EU-Taxonomy prescribes aggregation of company-level EU-Taxonomy-aligned financial metrics to the level of the financial product. Pre-contractual disclosures of environmentally sustainable investments prospectively have to include a percentage value describing the proportions of the invested companies’ economic activities that are considered in alignment to the EU-Taxonomy. OutlookThe EU-Taxonomy fundamentally alters non-financial transparency requirements of large companies.It enhances the transparency for the two objective, climate change mitigation and adaptation.

The technical screening criteria cover the contribution of the companies to these objectives in a very comprehensive way.

Also the next steps to develop screening criteria for the four remaining objective by the Sustainable Finance Platform of the EU are promising.

It is especially useful to align the review of the CSR-directive with the Taxonomy, an EU ecolabel, and the SFDR.

However, at this early stage, an evaluation of its effectiveness is not possible due to the lack of information about how it will be implemented. Hardly anything is known about the technical screening criteria concerning the four non-climate related environmental objectives.Exemplarily, it is not clear what type of economic activities substantially contribute the transition to a circular economy. In light of the rather inexplicit definition of “circular economy” as per Article 2(9) of the EU-Taxonomy, selecting such activities remains a major challenge. Aggravatingly, academic research on the functioning of a circular economy on the company-level of analysis is largely absent. This is most likely due to the lack of available data and the elusiveness of “circular economy” as an outcome variable in empirical research. The maintenance of products, materials and other resources for “as long as possible”, as described in the EU-Taxonomy, surely leaves considerable room for interpretation and requires further clarification by the platform on sustainable finance. Notably, such considerations were not within the scope of the TEG, which apart from the DNSH-principle, exclusively focused on the climate change related environmental objectives.More generally, the current regulatory landscape lacks a unified and distinct set of key terminologies. Overlapping concepts, such as “adverse sustainability impacts” (SFDR), “significant harm” (EU-Taxonomy), and “principle risks” (CSR-directive) may impair the preparation and the usefulness of non-financial disclosures. The European Sustainable Investment Forum (Eurosif) expresses similar concerns and recommends better aligning of references and definitions between the SFDR and the EU-Taxonomy.Looking ahead, the real impact of the EU-Taxonomy on the achievement of a climate neutral European economy by 2050 is rather uncertain. While the regulation substantially increases the transparency of economic activities contributing to environmental objectives, it does not mandate greater transparency regarding environmentally harmful activities.

In other words, companies will not have to report on whycertain economic activities are not EU-Taxonomy-aligned. Users of non-financial disclosure will not be able to differentiate between economic activities that barely miss technical thresholds and those that are actually very far away from it. This circumstance may hamper the efficient allocation of financial capital towards sustainable investments and thus diminish the contribution of financial markets to the transition towards a net-zero-emissions economy.The transition towards quantitative non-financial disclosures still constitutes a crucial milestone towards full corporate transparency and accountability. Yet, in an ideal world, the disclosure of financial metrics would reveal the true costs of environmental externalities. To this end, the Natural Capital Coalition and the Value Balancing Alliance call for the establishment of environmental generally accepted accounting principles (E-GAAP). However, inseparably linking financial and non-financial disclosures in a unified set of accounting principles continues to be an idealistic conception that is certainly not within the scope of the current regulatory landscape. The EU-Taxonomy progresses the visibility of environmentally responsible firms, but does little to nothing in exposing climate offenders and, more generally, corporate disregard for the environment.Right now a couple of sustainable initiatives appear simultaneously. E. g. the European Commission (DG Just) has invited feedback on its Sustainable Corporate Governance Initiative and has kickstarted an academic discussion on the role of the board in furthering sustainability issues. brief bioKerstin Lopatta is a full professor at the School of Business, Economics and Social Science at the University of Hamburg. Kerstin Lopatta has work experience as a consultant in a big 4 audit company and she had several research stays including City University Hong Kong and New York University Stern School of Business. Her work was published in international high ranked journals including Journal of Corporate Finance, Business & Society, Journal of Business Ethics, Journal of Risk Finance and Journal of Business Economics. She has several cooperations with global and small and medium-sized companies. In her current work she investiagtes the EU Taxonomy and its implications for financial accounting and non financial reporting. All opinions expressed are those of the author. investESG.eu is an independent and neutral platform dedicated to generating debate around ESG investing topics.